Gold Rush and The Charlestown Mining Company

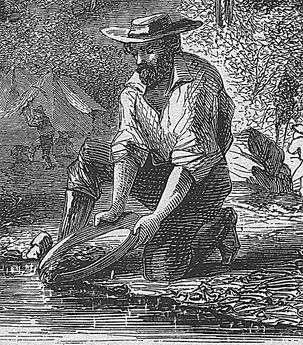

The Gold Rush "Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!" This, the most famous quote of the California Gold Rush was by San Francisco publisher and merchant Samuel Brannan; after he had hurriedly set up a store to sell gold prospecting supplies, January 24, 1848 James W. Marshall, a foreman working for Sacramento pioneer John Sutter, had found shiny metal in the tailrace of a lumber mill Marshall was building for Sutter on the American River. When tests showed that it was gold, Sutter expressed dismay; he wanted to keep the news quiet because he feared what would happen to his plans for an agricultural empire if there was a mass search for gold.

At the time gold was discovered, California was part of the Mexican territory of Alta California, but California was ceded to the U.S. after the end of the Mexican-American War with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848, less than two weeks after the discovery of gold.

On August 19, 1848, the New York Herald was the first major newspaper on the East Coast to report the discovery of gold. On December 5, 1848, President James Polk confirmed the discovery of gold in an address to Congress. Soon, waves of immigrants from around the world, later called the "forty-niners", invaded the Gold Country of California or "Mother Lode". As Sutter had feared, he was ruined; his workers left in search of gold, and squatters took over his land and stole his crops and cattle.

The first people to rush to the gold fields, beginning in the spring of 1848, were the residents of California themselves—primarily agriculturally oriented Americans and Europeans living in Northern California, along with Native Americans and some Californios (Spanish-speaking Californians). These first miners tended to be families in which everyone helped in the effort.

The largest group of forty-niners in 1849 was Americans, arriving by the tens of thousands overland across the continent and along various sailing routes (the name "forty-niner" was derived from the year 1849). Four principal routes were followed by forty-niners from the eastern United States to the gold fields of California—Cape Horn, Panama, Mexico, and the Southwest. Between them these routes probably carried a little more than half or more of the 20,000 emigrants who sought to reach California in 1849. Perhaps the best known, least expensive and most fully tested was the Southwest Route which utilized the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to St. Louis, the Missouri River from St. Louis to what is today Kansas City or St. Joseph on the border of Indian Country. From there hundreds of wagon trains powered by mules or oxen followed the Oregon and California Trial along the Platte River, past Fort Laramie, across the Continental Divide at South Pass in Wyoming and across the Green River. The trail then going either south of the Great Salt Lake or a northern route south of the Snake River. The trails converged and followed the Humboldt River to the Humboldt Desert and then pushed up the valley of the Truckee or Carson River over the Sierra Nevada, and into the valley of Sacramento River.

B. F. Washington, President, The Charlestown Virginia Mining Company

Gold Rush fever reached Jefferson Co., Virginia where three gold hunting companies were organized. The Harpers Ferry Company was organized by Col. Whiting, a Texas Ranger, and left for California February 23, 1849; The Shepherdstown Company whose president was Dr. Richard Parran, left in the Spring of 1849. On January 8, 1849, the following notice appeared in the Spirit of Jefferson, Charlestown, Virginia for the organization of a third mining company from Jefferson County.

“Ho, for California! It having been determined to organize a company for California whose principal pursuit shall be digging the soil for virgin gold, all who are desirous of joining the expedition, will meet at the law offices of B. F. Washington on Tuesday the 9th instant at seven in the evening. An opportunity is now afforded to active and energetic young men of bettering their pecuniary position and at the same time they may see the garden spot of the world.”[i]

Written with a tinge of “legalese” and flair intending to entice young wealth seeking adventurers, this notice attracted more than 100 qualified young men to the law offices of Benjamin Franklin Washington. The intended quota of 60 men was chosen to join The Charlestown Virginia Mining Company. Benjamin Franklin Washington was elected President of the company. The membership quota was soon increased to 70 members and had swelled to a membership of 85 before the expedition left Charlestown on March 27 aboard a special train of the Winchester & Potomac Railroad.

B. F. Washington was one of thirteen children of John Thornton Augustine Washington and Elizabeth Conrad Bedinger of “Cedar Lawn” near Charlestown. Elizabeth Conrad Bedinger was the daughter of Lt. Daniel Bedinger and Sarah Rutherford of “Bedford” at Shepherdstown, Virginia. B. F. Washington, born 7 April 1820, was educated chiefly at the Charlestown Academy. He studied law and at an early age entered upon its practice. He was a chief contributor to the “Spirit of Jefferson”, a democratic newspaper of considerable reputation published in Charlestown. He was sole executor of his father’s estate and entered upon the responsibilities and duties of its administration at the age of 21.[ii]

The Charlestown Company was joined by Lawrence Berry Washington, older brother of B. F. Washington. Lawrence Berry Washington, born 8 November 1811, never married. He was a lawyer by profession. He had served as a lieutenant in Colonel John Frances Hamtramck’s regiment of Virginia infantry during the Mexican War.

A cousin of the brothers Lawrence Berry and Benjamin Franklin Washington, by the name of Edward Washington McIlhany of Loudon County, Virginia, also joined the company. His mother, Mary Ann Washington was the daughter of Edward Washington and Elizabeth Sanford. Welles (1879, pp. 308-314)[iii] believes Edward Washington McIlhany to be a descendant of Laurence Washington, the immigrant and brother of Col. John Washington. Edward Washington McIlhany, many years after the Gold Rush, wrote the story of his Gold Rush adventures “Recollections of a ‘49er, A Quaint and Thrilling Narrative of a Trip Across the Plains, and the Life in the California Gold Fields During the Stirring Days following the Discovery of Gold in the Far West.”[iv]

A fourth Washington joined the company, a second cousin of Benjamin Franklin Washington; Thomas West Washington was the great-grandson of Samuel Washington and his third wife Anne Steptoe. Benjamin Franklin Washington was the great-grandson of Samuel Washington and his fourth wife Mildred Thornton.

The expedition was planned in detail under the watchful supervision of Benjamin Franklin Washington. Each member paid a fee of $300 and was given a knapsack bearing the company name for carrying their clothes and personal items. Each member was limited to 50 pounds of personal gear. A list of clothing was recommended for each member to bring. The company purchased and provided each member with a shotgun or a rifle and a pair of revolvers. The Company purchased a small 6 pound cannon which it lugged all the way to California. The mining supplies for the Company were purchased in Baltimore and shipped by sea around Cape Horn to San Francisco. The Company had sixteen wagons built for them in St. Joseph, Missouri. Two of their wagons beds constructed as pontoons made of sheet iron. The wagons could be disassembled and the pontoons wagons used as boats in ferrying across large streams that might be encountered on the journey.

Railroad Train, Stage Coach, Steamboat, and Mule Train

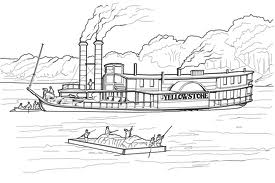

The train from Charlestown took the members of the company as far as Harpers Ferry where they boarded the Baltimore & Ohio which carried the company to the end of the rail line at Cumberland in western Maryland. From Cumberland they took stage coaches across the Allegheny Mountains to Brownsville on the Ohio River. From Brownsville, they took passage on a steamer bound for St. Louis. McIlhany[v] recalled that there was a band on the boat and they enjoyed the music going down the river, especially so when night came the Negro deck hands sang old plantation songs.

They arrived safely in St. Louis, which at that time was a small town settled mostly by French. There the company bought supplies for the journey ahead. The supplies were loaded on the steam boat Embassy and the company journeyed up the Missouri River. Alonzo Delano[vi], who was with a different expedition, was on the Embassy with the Charlestown Mining Company men. Delano wrote, “There was a great crowd of adventurers on the Embassy. Nearly every berth was full, and not only every settee and table occupied at night, but the cabin floor was covered by the sleeping emigrants. The decks were covered with wagons, mules, oxen, and mining implements and the hold was filled with supplies. But this was the condition of every boat—for since the invasion of Rome by the Goths, such a deluge of mortals had not been witnessed, as was now pouring from the States to the various points of departure for the golden shores of California. Visions of sudden and immense wealth were dancing in the imagination of these anxious seekers of fortunes, and I must confess that I was not entirely free from such dreams… Our first day out was spent in these pleasing reflections, and the song and the jest went round with glee—while the toil, the dangers and the hardships, yet to come, were not thought of, for they were not yet understood. On the second day out the sound of mirth was checked and we were struck with alarm—the cholera is on board”[vii]. Thomas Washington had come down with Asiatic cholera and died 12 April 1849.[viii] Thomas Washington, a member of the Charlestown Mining Company had been infected with the dread disease Asiatic cholera during the brief stay in St. Louis. Although every attention was rendered which skill and science could give, the symptoms grew worse, and he expired at ten o’clock on the morning after he was taken ill. A burial spot was found in a gorge between two lofty hills. A procession was formed by all the passengers who solemnly proceeded to the grave. And an intimate friend of the deceased, probably his kinsman B .F. Washington, read the Episcopal burial service, throughout which there was drizzling rain. [ix]

The journey on the Embassy continued past Westport, where Kansas City, Missouri now stands. Westport was at the northern terminus of the Santa Fe Trail and a landing place for river steamboats. At Westport the Missouri River takes a turn northward toward St. Joseph about a hundred miles north of Westport. At St. Joseph the company assembled the mules and the wagons which had been purchased by members of the company which had been assigned those duties.

[i] Perks, Douglas P., Ho, for California! The Charlestown Virginia Mining Company, Magazine of the Jefferson County Historical Society, vol. LXXIII, December 2007, pp. 16-23.

[ii] Washington, Thornton Augustine, 1891, A Genealogical History beginning with Colonel John Washington, the Emigrant, and Head of the Washington Family in America, Press of McGill & Wallace, 71 p.

[iii] Welles, Albert, 1879, The Pedigree and History of the Washington Family, Society Library, New York, 370 p.

[iv] McIlhany, Edward Washington, 1908, Recollections of a ‘49er, A Quaint and Thrilling Narrative of a Trip Across the Plains, and the Life in the California Gold Fields During the Stirring Days following the Discovery of Gold in the Far West, Hailman Printing Company, Kansas City, Missouri, 212p.

[v] McIlhany, Edward Washington, 1908, Recollections of a ‘49er, A Quaint and Thrilling Narrative of a Trip Across the Plains, and the Life in the California Gold Fields During the Stirring Days following the Discovery of Gold in the Far West, Hailman Printing Company, Kansas City, Missouri, 212p.

[vi] Delano, A., 1857, Life on the Plains and Among the Diggings; being Scenes and Adventures of an Overland Journey to California: Miller Orton & Co., 384 p.

[vii] Delano, A., 1857, Life on the Plains and Among the Diggings; being Scenes and Adventures of an Overland Journey to California: Miller Orton & Co., 384 p.

[viii] Welles, Albert, 1879, The Pedigree and History of the Washington Family, Society Library, New York, 370 p.

[ix] Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p., p. 33. and Delano, A., 1857, Life on the Plains and Among the Diggings; being Scenes and Adventures of an Overland Journey to California: Miller Orton & Co., 384 p., pp. 14-16.

At the time gold was discovered, California was part of the Mexican territory of Alta California, but California was ceded to the U.S. after the end of the Mexican-American War with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848, less than two weeks after the discovery of gold.

On August 19, 1848, the New York Herald was the first major newspaper on the East Coast to report the discovery of gold. On December 5, 1848, President James Polk confirmed the discovery of gold in an address to Congress. Soon, waves of immigrants from around the world, later called the "forty-niners", invaded the Gold Country of California or "Mother Lode". As Sutter had feared, he was ruined; his workers left in search of gold, and squatters took over his land and stole his crops and cattle.

The first people to rush to the gold fields, beginning in the spring of 1848, were the residents of California themselves—primarily agriculturally oriented Americans and Europeans living in Northern California, along with Native Americans and some Californios (Spanish-speaking Californians). These first miners tended to be families in which everyone helped in the effort.

The largest group of forty-niners in 1849 was Americans, arriving by the tens of thousands overland across the continent and along various sailing routes (the name "forty-niner" was derived from the year 1849). Four principal routes were followed by forty-niners from the eastern United States to the gold fields of California—Cape Horn, Panama, Mexico, and the Southwest. Between them these routes probably carried a little more than half or more of the 20,000 emigrants who sought to reach California in 1849. Perhaps the best known, least expensive and most fully tested was the Southwest Route which utilized the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to St. Louis, the Missouri River from St. Louis to what is today Kansas City or St. Joseph on the border of Indian Country. From there hundreds of wagon trains powered by mules or oxen followed the Oregon and California Trial along the Platte River, past Fort Laramie, across the Continental Divide at South Pass in Wyoming and across the Green River. The trail then going either south of the Great Salt Lake or a northern route south of the Snake River. The trails converged and followed the Humboldt River to the Humboldt Desert and then pushed up the valley of the Truckee or Carson River over the Sierra Nevada, and into the valley of Sacramento River.

B. F. Washington, President, The Charlestown Virginia Mining Company

Gold Rush fever reached Jefferson Co., Virginia where three gold hunting companies were organized. The Harpers Ferry Company was organized by Col. Whiting, a Texas Ranger, and left for California February 23, 1849; The Shepherdstown Company whose president was Dr. Richard Parran, left in the Spring of 1849. On January 8, 1849, the following notice appeared in the Spirit of Jefferson, Charlestown, Virginia for the organization of a third mining company from Jefferson County.

“Ho, for California! It having been determined to organize a company for California whose principal pursuit shall be digging the soil for virgin gold, all who are desirous of joining the expedition, will meet at the law offices of B. F. Washington on Tuesday the 9th instant at seven in the evening. An opportunity is now afforded to active and energetic young men of bettering their pecuniary position and at the same time they may see the garden spot of the world.”[i]

Written with a tinge of “legalese” and flair intending to entice young wealth seeking adventurers, this notice attracted more than 100 qualified young men to the law offices of Benjamin Franklin Washington. The intended quota of 60 men was chosen to join The Charlestown Virginia Mining Company. Benjamin Franklin Washington was elected President of the company. The membership quota was soon increased to 70 members and had swelled to a membership of 85 before the expedition left Charlestown on March 27 aboard a special train of the Winchester & Potomac Railroad.

B. F. Washington was one of thirteen children of John Thornton Augustine Washington and Elizabeth Conrad Bedinger of “Cedar Lawn” near Charlestown. Elizabeth Conrad Bedinger was the daughter of Lt. Daniel Bedinger and Sarah Rutherford of “Bedford” at Shepherdstown, Virginia. B. F. Washington, born 7 April 1820, was educated chiefly at the Charlestown Academy. He studied law and at an early age entered upon its practice. He was a chief contributor to the “Spirit of Jefferson”, a democratic newspaper of considerable reputation published in Charlestown. He was sole executor of his father’s estate and entered upon the responsibilities and duties of its administration at the age of 21.[ii]

The Charlestown Company was joined by Lawrence Berry Washington, older brother of B. F. Washington. Lawrence Berry Washington, born 8 November 1811, never married. He was a lawyer by profession. He had served as a lieutenant in Colonel John Frances Hamtramck’s regiment of Virginia infantry during the Mexican War.

A cousin of the brothers Lawrence Berry and Benjamin Franklin Washington, by the name of Edward Washington McIlhany of Loudon County, Virginia, also joined the company. His mother, Mary Ann Washington was the daughter of Edward Washington and Elizabeth Sanford. Welles (1879, pp. 308-314)[iii] believes Edward Washington McIlhany to be a descendant of Laurence Washington, the immigrant and brother of Col. John Washington. Edward Washington McIlhany, many years after the Gold Rush, wrote the story of his Gold Rush adventures “Recollections of a ‘49er, A Quaint and Thrilling Narrative of a Trip Across the Plains, and the Life in the California Gold Fields During the Stirring Days following the Discovery of Gold in the Far West.”[iv]

A fourth Washington joined the company, a second cousin of Benjamin Franklin Washington; Thomas West Washington was the great-grandson of Samuel Washington and his third wife Anne Steptoe. Benjamin Franklin Washington was the great-grandson of Samuel Washington and his fourth wife Mildred Thornton.

The expedition was planned in detail under the watchful supervision of Benjamin Franklin Washington. Each member paid a fee of $300 and was given a knapsack bearing the company name for carrying their clothes and personal items. Each member was limited to 50 pounds of personal gear. A list of clothing was recommended for each member to bring. The company purchased and provided each member with a shotgun or a rifle and a pair of revolvers. The Company purchased a small 6 pound cannon which it lugged all the way to California. The mining supplies for the Company were purchased in Baltimore and shipped by sea around Cape Horn to San Francisco. The Company had sixteen wagons built for them in St. Joseph, Missouri. Two of their wagons beds constructed as pontoons made of sheet iron. The wagons could be disassembled and the pontoons wagons used as boats in ferrying across large streams that might be encountered on the journey.

Railroad Train, Stage Coach, Steamboat, and Mule Train

The train from Charlestown took the members of the company as far as Harpers Ferry where they boarded the Baltimore & Ohio which carried the company to the end of the rail line at Cumberland in western Maryland. From Cumberland they took stage coaches across the Allegheny Mountains to Brownsville on the Ohio River. From Brownsville, they took passage on a steamer bound for St. Louis. McIlhany[v] recalled that there was a band on the boat and they enjoyed the music going down the river, especially so when night came the Negro deck hands sang old plantation songs.

They arrived safely in St. Louis, which at that time was a small town settled mostly by French. There the company bought supplies for the journey ahead. The supplies were loaded on the steam boat Embassy and the company journeyed up the Missouri River. Alonzo Delano[vi], who was with a different expedition, was on the Embassy with the Charlestown Mining Company men. Delano wrote, “There was a great crowd of adventurers on the Embassy. Nearly every berth was full, and not only every settee and table occupied at night, but the cabin floor was covered by the sleeping emigrants. The decks were covered with wagons, mules, oxen, and mining implements and the hold was filled with supplies. But this was the condition of every boat—for since the invasion of Rome by the Goths, such a deluge of mortals had not been witnessed, as was now pouring from the States to the various points of departure for the golden shores of California. Visions of sudden and immense wealth were dancing in the imagination of these anxious seekers of fortunes, and I must confess that I was not entirely free from such dreams… Our first day out was spent in these pleasing reflections, and the song and the jest went round with glee—while the toil, the dangers and the hardships, yet to come, were not thought of, for they were not yet understood. On the second day out the sound of mirth was checked and we were struck with alarm—the cholera is on board”[vii]. Thomas Washington had come down with Asiatic cholera and died 12 April 1849.[viii] Thomas Washington, a member of the Charlestown Mining Company had been infected with the dread disease Asiatic cholera during the brief stay in St. Louis. Although every attention was rendered which skill and science could give, the symptoms grew worse, and he expired at ten o’clock on the morning after he was taken ill. A burial spot was found in a gorge between two lofty hills. A procession was formed by all the passengers who solemnly proceeded to the grave. And an intimate friend of the deceased, probably his kinsman B .F. Washington, read the Episcopal burial service, throughout which there was drizzling rain. [ix]

The journey on the Embassy continued past Westport, where Kansas City, Missouri now stands. Westport was at the northern terminus of the Santa Fe Trail and a landing place for river steamboats. At Westport the Missouri River takes a turn northward toward St. Joseph about a hundred miles north of Westport. At St. Joseph the company assembled the mules and the wagons which had been purchased by members of the company which had been assigned those duties.

[i] Perks, Douglas P., Ho, for California! The Charlestown Virginia Mining Company, Magazine of the Jefferson County Historical Society, vol. LXXIII, December 2007, pp. 16-23.

[ii] Washington, Thornton Augustine, 1891, A Genealogical History beginning with Colonel John Washington, the Emigrant, and Head of the Washington Family in America, Press of McGill & Wallace, 71 p.

[iii] Welles, Albert, 1879, The Pedigree and History of the Washington Family, Society Library, New York, 370 p.

[iv] McIlhany, Edward Washington, 1908, Recollections of a ‘49er, A Quaint and Thrilling Narrative of a Trip Across the Plains, and the Life in the California Gold Fields During the Stirring Days following the Discovery of Gold in the Far West, Hailman Printing Company, Kansas City, Missouri, 212p.

[v] McIlhany, Edward Washington, 1908, Recollections of a ‘49er, A Quaint and Thrilling Narrative of a Trip Across the Plains, and the Life in the California Gold Fields During the Stirring Days following the Discovery of Gold in the Far West, Hailman Printing Company, Kansas City, Missouri, 212p.

[vi] Delano, A., 1857, Life on the Plains and Among the Diggings; being Scenes and Adventures of an Overland Journey to California: Miller Orton & Co., 384 p.

[vii] Delano, A., 1857, Life on the Plains and Among the Diggings; being Scenes and Adventures of an Overland Journey to California: Miller Orton & Co., 384 p.

[viii] Welles, Albert, 1879, The Pedigree and History of the Washington Family, Society Library, New York, 370 p.

[ix] Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p., p. 33. and Delano, A., 1857, Life on the Plains and Among the Diggings; being Scenes and Adventures of an Overland Journey to California: Miller Orton & Co., 384 p., pp. 14-16.

Breaking Mules in St. Joe

The wagon trains that assembled in St. Joseph for the journey across the country to the gold fields used various modes of animal power to pull their belongings and supplies across the barely charted expanse of the west. Oxen, horses and mules were the three accessible choices. Horses were preferred by most as saddle animals for scouting, carrying a single individual, but were not strong or durable enough as a draft animal for pulling heavy loads. Oxen were strong draft animals, relatively easy to handle, and could be depended on day after day to pull heavy loads. But, oxen were slow draft animals. Mules were strong, durable ad could pull heavy loads long distances. And they could outdistance oxen and horses as draft animals. The Virginians discovered mules were not the easiest of draft animals to train. The teamsters who worked with the mules had to learn and adapt to the peculiar habits and eccentricities of each mule before gaining their cooperation and eventually establishing a trusted relationship.

The company had bought more than a hundred mules, some horses and sixteen wagons. The mules were wild and unbroken and until the spring grass should grow up in sufficient abundance to provide forage for their animals, there was nothing to do but camp at St. Joseph and break mules. This activity went far to relieve the monotony, for a Missouri mule was a formidable adversary, and the business of taming him was a task that evoked complaint from many migrants. The company was in St. Joseph nearly a month with the men getting acquainted with their mules.[i] Personal accounts of the getting acquainted process was noted in the log of Geiger[ii], who noted in the early part of the journey, that several men had taken lofty tumblings from off the mules’ back. “Capt. Keeling took a high fall from an old white mule, and a man by the name of Miller was thrown “Hell, west and crooked”.

Vincent Geiger and Dr. Bryarly[iii] kept a daily record of the excursion, describing events, encounters with animals, Indians, distance traveled, and what would ordinarily be very mundane things such as sources of fresh water, firewood and sufficient grass for their draft animals. Now, in their circumstance, these very mundane things were of paramount importance to their progress and survival. Some fifty years after the journey, another member of the company, Edward Washington McIlhany wrote a book of his remembrances of the trip to California and his experiences in the gold fields. It is clear from the writings of Geiger and Briarly, Washington, Aden and others who recorded tales of wagon trains to the gold fields that the Charlestown Company was a particularly well-organized, well-outfitted, and well-led party. It was one of the few which did not disintegrate to some degree during the journey. The methods and the success of this party, by comparison with others, tend to illuminate certain problems of the overland journey.[iv]

The Charlestown Company had elected officers, and adopted a Constitution. The board of officers headed was by Benjamin Franklin Washington, President, with First, Second and Third Commanders, a Treasurer, Quarter Master, and Secretary. The Surgeon was Dr. Wake Bryarly, a most important member of the company. Moreover, the general membership of the company had been selected among the many applicants for their physical ability and character; men who could endure the hardships of such an adventure. At least six of them had been officers in the Mexican War with experience in the American West.[v]

As a matter of course, the wagon train selected a captain, and it appears that every company for more than twenty years thereafter must have followed this example. The danger of Indians or of lawless whites, the necessity of maintaining some formation in travelling and of regularizing the guard duty, all combined to make military arrangement universal. Robert H. Keeling, the First Commander was initially designated to be the captain. Before the company left St. Joseph, some members of the Company met a Mr. Frank Smith who had been over the Oregon Trail as early as 1845 and who had learned the art of successful overland travel. The Charlestown Company secured the services of this talented frontiersman as a guide and it later elected him to member with full financial rights in the Company. Much of the success of the journey resulted from his leadership.[vi]

Seven wagons of the company left their encampment on the west bank of the Missouri River opposite St. Joseph on Thursday, May 10th, 1849 and encamped about seven miles from the river at a place called “the Bluffs”. The remainder of the wagons joined the group the next day. The wagon train branded their stock with the initials “V C” at their encampment near a spring which they named “Branding Spring”. The company traveled westward, gradually trending northward following the Kansas River, the Big Blue and then the Little Blue into Nebraska. The Little Blue led them to the Platte River near Ft. Kearney. There they followed the Mormon trail along the course of the Platte River to the mouth of the South Platte River which led them to Fort Laramie.

From Dr. Bryarly’s log: ”Wednesday, May 16th. Got off about 7o’clok A.M. & pursued the ridge & rolling country, the grass good. Passed several detachments of Government troops & wagons on their way to California & Oregon. The guide of the Government train, a Mr. Hendricks was shot by an Indian the day before—severely but not dangerously wounded. Continued to catch up and pass emigrants. Got to camp about 4 o’clock P.M. Scarce of wood & water.

“An Iowa Chief, some squaws & two boys visited our camp. The Chief had seven wives, much children. The boys shot well with bow & arrow. Our mess fed them, for which they seemed little thankful.”

“West of the wooded area, dried buffalo dung, known as buffalo chips or bois de vache became the standard fuel. “ An emigrant wrote home, ‘You would laugh, I know, to see me going along with a bag on my back gathering Buffalo dung to cook with, but we have to do it. The darn stuff burns fine in a stove.”

The following is taken from the log of the Doctor Bryarly as the wagon train followed the Platte River across what is today Nebraska. [vii] “Friday, June 1st. This is a beautiful morning. The sun rose warm & good. A strong bracing wind made travel agreeable. … A gang of 15 or 20 antelopes were seen today, but too far off to shoot at. …We have seen very few buffalo, but their trails are found at every step. …One of the men just brought in a Prairie wolf [coyote] but which looks more like a red fox—the same color, but of large size than those found in our country. A few miles from where we nooned, we came across a spring of pure, good, cold water, which was relished by our boys in fine style. We here filled our casks & were loath to leave the spot. Wood was procured here, & after a travel of a few miles, we went into camp near the river with good grass for our mules. Dug for and obtained water, but it was rather brackish. …Distance, 18 miles.”

“Saturday, June 2nd. Today, we lay up for the purpose of resting our stock, which are much fatigued. There is but little rest, however, for the men. Washing & cooking is the order of the day. These are the great works, whilst some are busily engaged I writing, reading, cleaning guns, pistols, &c, others shooting mark, some fishing, & one or two singing & fiddling. We have shod some mules & horses. This morning early, a tremendous large wolf passed near our camp, but he escaped the rifles of our marksmen. The day has been pleasant & clear & all look happy & joyful. We have been living high today. Lambs quarter greens, stewed peaches, rive & molasses were served up by every mess. Some have had peach pies.”

“Whilst four stock were grazing, and some few men reposing in camp, the poetic talent of our president, B. F. Washington, Esq., was brought into play & produced the following beautiful & feeling lines which I have taken the liberty to copy into my book, feeling assured that they will be read with interest & pleasure:

To My Native State

Virginia, O Virginia, still thy valley fair I see,

While each hour with “weary step & slow” I’m wandering from thee;

As visions of departed years come swiftly o’er my mind,

They bring to me each hallow’d spot which I have left behind.

“Tis not because thy hills are green, thy valleys fair to see,

Thy forests clothed with varied tints & fill’d with harmony,

“Tis not because thy skies are bright as Italy’s in hue,

Or on thy distant mountains rests a veil of shadowy blue,

‘Tis not that thou hast ever been fair Freedom’s dwelling place,

Whence warriors brave & statesmen too, a noble lineage trace,

Nor is it that the fire first burned, thy sacred hills upon,

Whose light with hallow’d radiance now to all the world hath gone.

Ah no, not these, nor other charms my muse might well proclaim,

Which throws while now I think of thee, a magic round thy name;

There’s something more enchanting still that bids my spirit flee,

O’er all the weary waste of miles betwixt myself & thee.

Just where a smiling landscape looks upon thy mountains blue,

Where met the waters on their way and swept their barriers through,

There dwelt a maid whose sunny face, & soul of guileless love,

We stood beside the alter & the priest pronounced us one,

And I felt that I had all the world in her whom thus I won.

And now four years have nearly passed since on that happy day,

My stormy youth subsided to the peaceful calm of May;

And cherubs two have bless’d my home—as noble boys I wean,

As ever round the alter of domestic love were seen.

And thus I thought my cup of bliss was full & I would glide,

With sweet contentment, peace & love, upon life’s onward tide;

But ah! A change came o’er me & I have left my home,

A wanderer to a stranger land, mid howling wastes to roam.

Upon Pacific’s distant shores is heard a startling cry,

A sound that wakes the nations up as swift the tidings fly;

An El Dorado of untold wealth—a land whose soil is gold,

Full many a glittering dram of wealth to mortal eyes unfold.

O gold! How mighty is thy sway, how potent is thy rod!

Decrepit age & tender youth acknowledge thee a God;

At thy command the world is sway’d, as on the deep blue sea,

The Storm King rules the elements that roll so restlessly.

And see, the crowd is rushing now across the arid plain,

All urged by different passions on, yet most by thirst of gain;

And I, my home & native state, have left thy genial shade,

To throw my banner to the breeze where wealth, like dreams, is made.”

The wagon trains that assembled in St. Joseph for the journey across the country to the gold fields used various modes of animal power to pull their belongings and supplies across the barely charted expanse of the west. Oxen, horses and mules were the three accessible choices. Horses were preferred by most as saddle animals for scouting, carrying a single individual, but were not strong or durable enough as a draft animal for pulling heavy loads. Oxen were strong draft animals, relatively easy to handle, and could be depended on day after day to pull heavy loads. But, oxen were slow draft animals. Mules were strong, durable ad could pull heavy loads long distances. And they could outdistance oxen and horses as draft animals. The Virginians discovered mules were not the easiest of draft animals to train. The teamsters who worked with the mules had to learn and adapt to the peculiar habits and eccentricities of each mule before gaining their cooperation and eventually establishing a trusted relationship.

The company had bought more than a hundred mules, some horses and sixteen wagons. The mules were wild and unbroken and until the spring grass should grow up in sufficient abundance to provide forage for their animals, there was nothing to do but camp at St. Joseph and break mules. This activity went far to relieve the monotony, for a Missouri mule was a formidable adversary, and the business of taming him was a task that evoked complaint from many migrants. The company was in St. Joseph nearly a month with the men getting acquainted with their mules.[i] Personal accounts of the getting acquainted process was noted in the log of Geiger[ii], who noted in the early part of the journey, that several men had taken lofty tumblings from off the mules’ back. “Capt. Keeling took a high fall from an old white mule, and a man by the name of Miller was thrown “Hell, west and crooked”.

Vincent Geiger and Dr. Bryarly[iii] kept a daily record of the excursion, describing events, encounters with animals, Indians, distance traveled, and what would ordinarily be very mundane things such as sources of fresh water, firewood and sufficient grass for their draft animals. Now, in their circumstance, these very mundane things were of paramount importance to their progress and survival. Some fifty years after the journey, another member of the company, Edward Washington McIlhany wrote a book of his remembrances of the trip to California and his experiences in the gold fields. It is clear from the writings of Geiger and Briarly, Washington, Aden and others who recorded tales of wagon trains to the gold fields that the Charlestown Company was a particularly well-organized, well-outfitted, and well-led party. It was one of the few which did not disintegrate to some degree during the journey. The methods and the success of this party, by comparison with others, tend to illuminate certain problems of the overland journey.[iv]

The Charlestown Company had elected officers, and adopted a Constitution. The board of officers headed was by Benjamin Franklin Washington, President, with First, Second and Third Commanders, a Treasurer, Quarter Master, and Secretary. The Surgeon was Dr. Wake Bryarly, a most important member of the company. Moreover, the general membership of the company had been selected among the many applicants for their physical ability and character; men who could endure the hardships of such an adventure. At least six of them had been officers in the Mexican War with experience in the American West.[v]

As a matter of course, the wagon train selected a captain, and it appears that every company for more than twenty years thereafter must have followed this example. The danger of Indians or of lawless whites, the necessity of maintaining some formation in travelling and of regularizing the guard duty, all combined to make military arrangement universal. Robert H. Keeling, the First Commander was initially designated to be the captain. Before the company left St. Joseph, some members of the Company met a Mr. Frank Smith who had been over the Oregon Trail as early as 1845 and who had learned the art of successful overland travel. The Charlestown Company secured the services of this talented frontiersman as a guide and it later elected him to member with full financial rights in the Company. Much of the success of the journey resulted from his leadership.[vi]

Seven wagons of the company left their encampment on the west bank of the Missouri River opposite St. Joseph on Thursday, May 10th, 1849 and encamped about seven miles from the river at a place called “the Bluffs”. The remainder of the wagons joined the group the next day. The wagon train branded their stock with the initials “V C” at their encampment near a spring which they named “Branding Spring”. The company traveled westward, gradually trending northward following the Kansas River, the Big Blue and then the Little Blue into Nebraska. The Little Blue led them to the Platte River near Ft. Kearney. There they followed the Mormon trail along the course of the Platte River to the mouth of the South Platte River which led them to Fort Laramie.

From Dr. Bryarly’s log: ”Wednesday, May 16th. Got off about 7o’clok A.M. & pursued the ridge & rolling country, the grass good. Passed several detachments of Government troops & wagons on their way to California & Oregon. The guide of the Government train, a Mr. Hendricks was shot by an Indian the day before—severely but not dangerously wounded. Continued to catch up and pass emigrants. Got to camp about 4 o’clock P.M. Scarce of wood & water.

“An Iowa Chief, some squaws & two boys visited our camp. The Chief had seven wives, much children. The boys shot well with bow & arrow. Our mess fed them, for which they seemed little thankful.”

“West of the wooded area, dried buffalo dung, known as buffalo chips or bois de vache became the standard fuel. “ An emigrant wrote home, ‘You would laugh, I know, to see me going along with a bag on my back gathering Buffalo dung to cook with, but we have to do it. The darn stuff burns fine in a stove.”

The following is taken from the log of the Doctor Bryarly as the wagon train followed the Platte River across what is today Nebraska. [vii] “Friday, June 1st. This is a beautiful morning. The sun rose warm & good. A strong bracing wind made travel agreeable. … A gang of 15 or 20 antelopes were seen today, but too far off to shoot at. …We have seen very few buffalo, but their trails are found at every step. …One of the men just brought in a Prairie wolf [coyote] but which looks more like a red fox—the same color, but of large size than those found in our country. A few miles from where we nooned, we came across a spring of pure, good, cold water, which was relished by our boys in fine style. We here filled our casks & were loath to leave the spot. Wood was procured here, & after a travel of a few miles, we went into camp near the river with good grass for our mules. Dug for and obtained water, but it was rather brackish. …Distance, 18 miles.”

“Saturday, June 2nd. Today, we lay up for the purpose of resting our stock, which are much fatigued. There is but little rest, however, for the men. Washing & cooking is the order of the day. These are the great works, whilst some are busily engaged I writing, reading, cleaning guns, pistols, &c, others shooting mark, some fishing, & one or two singing & fiddling. We have shod some mules & horses. This morning early, a tremendous large wolf passed near our camp, but he escaped the rifles of our marksmen. The day has been pleasant & clear & all look happy & joyful. We have been living high today. Lambs quarter greens, stewed peaches, rive & molasses were served up by every mess. Some have had peach pies.”

“Whilst four stock were grazing, and some few men reposing in camp, the poetic talent of our president, B. F. Washington, Esq., was brought into play & produced the following beautiful & feeling lines which I have taken the liberty to copy into my book, feeling assured that they will be read with interest & pleasure:

To My Native State

Virginia, O Virginia, still thy valley fair I see,

While each hour with “weary step & slow” I’m wandering from thee;

As visions of departed years come swiftly o’er my mind,

They bring to me each hallow’d spot which I have left behind.

“Tis not because thy hills are green, thy valleys fair to see,

Thy forests clothed with varied tints & fill’d with harmony,

“Tis not because thy skies are bright as Italy’s in hue,

Or on thy distant mountains rests a veil of shadowy blue,

‘Tis not that thou hast ever been fair Freedom’s dwelling place,

Whence warriors brave & statesmen too, a noble lineage trace,

Nor is it that the fire first burned, thy sacred hills upon,

Whose light with hallow’d radiance now to all the world hath gone.

Ah no, not these, nor other charms my muse might well proclaim,

Which throws while now I think of thee, a magic round thy name;

There’s something more enchanting still that bids my spirit flee,

O’er all the weary waste of miles betwixt myself & thee.

Just where a smiling landscape looks upon thy mountains blue,

Where met the waters on their way and swept their barriers through,

There dwelt a maid whose sunny face, & soul of guileless love,

We stood beside the alter & the priest pronounced us one,

And I felt that I had all the world in her whom thus I won.

And now four years have nearly passed since on that happy day,

My stormy youth subsided to the peaceful calm of May;

And cherubs two have bless’d my home—as noble boys I wean,

As ever round the alter of domestic love were seen.

And thus I thought my cup of bliss was full & I would glide,

With sweet contentment, peace & love, upon life’s onward tide;

But ah! A change came o’er me & I have left my home,

A wanderer to a stranger land, mid howling wastes to roam.

Upon Pacific’s distant shores is heard a startling cry,

A sound that wakes the nations up as swift the tidings fly;

An El Dorado of untold wealth—a land whose soil is gold,

Full many a glittering dram of wealth to mortal eyes unfold.

O gold! How mighty is thy sway, how potent is thy rod!

Decrepit age & tender youth acknowledge thee a God;

At thy command the world is sway’d, as on the deep blue sea,

The Storm King rules the elements that roll so restlessly.

And see, the crowd is rushing now across the arid plain,

All urged by different passions on, yet most by thirst of gain;

And I, my home & native state, have left thy genial shade,

To throw my banner to the breeze where wealth, like dreams, is made.”

|

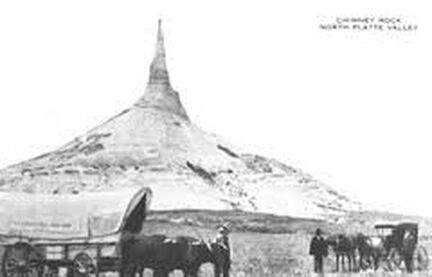

On June 11 the men camped at Chimney Rock, on which they found many names either cut or painted, among them the name of Captain Smith, cut there in 1845.

Chimney Rock rising 470 feet above the North Platte River Valley stands as the most celebrated of all natural formations along the overland routes to California, Oregon, and Utah. Chimney Rock served as an early landmark for traders, trappers, and 49'ers as they made their way from the Missouri River to the Rocky Mountains.

|

|

While following the Platte River, Tuesday, June 12th, Bryarly[viii] relates the encounter with a Mr. Robidoux, who was keeping a store and blacksmith shop and trading post. “He is married to a Sioux squaw & has several children. For goods of every description he charges the most exorbitant prices, & for work, truly extortionate.“

[i] McIlhany, Edward Washington, 1908, Recollections of a ‘49er, A Quaint and Thrilling Narrative of a Trip Across the Plains, and the Life in the California Gold Fields During the Stirring Days following the Discovery of Gold in the Far West, Hailman Printing Company, Kansas City, Missouri, 212p. and Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p.

[ii] Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p.

[iii] Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p.

[iv] Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p., p. 33., p. viii.

[v] Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p., p. 12.

[vi] Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p., p. 35.

[vii]Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p., p. 92-96.

[viii] Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p., p. 105.

[ii] Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p.

[iii] Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p.

[iv] Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p., p. 33., p. viii.

[v] Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p., p. 12.

[vi] Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p., p. 35.

[vii]Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p., p. 92-96.

[viii] Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p., p. 105.

Green River Crossing

The Charlestown Company wagon train arrived at the Green River Monday, July 2nd. McIlhany[i] relates the arrival and the crossing of the Green River using the pontoons with which the company had come equipped.

“We finally reached Green River, which is in Utah. A large Beautiful valley with a pretty stream. Here we first used our iron boats in crossing a stream. We placed everything in the boats except the mules and horses, and they swam the river. There we made our camp. The next day was the fourth of July, and there were a great many emigrants there resting. Up and down the stream they were camped about, three thousand strong. We rested all that day, engaged in cooking, sewing, and washing. Tom Moore, from Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, was selected as orator of the day. He stood on a large stump and had an Indian pole in his left hand to steady himself with. Being the Fourth of July, our quartermaster issued some whisky rations. Some had more or less, and some didn’t drink. We hadn’t had our little cannon out of the wagon since we started, and we concluded that we would take it out that day and chain it to the stump. Moore felt pretty good, felling the effects of his whisky, and every time that he would say anything patriotic would touch the little cannon off, and the echo would bellow up and down the valley. The Indians, when they heard that cannon, would not come anywhere near us. They got out of the way. Some of the boys concluded that they would steal the cannon and throw it into the river, so that they would no haul it any further. Others found out what they were up to and blocked their game, putting the little cannon back in the wagon.

“There were many there that never had seen or heard of a cannon before, and they were very much interested in the proceedings of the day. It was a day that we all enjoyed very much. Although extremely anxious to get to the promised land of gold, nevertheless we always enjoyed a rest. We never traveled on Sunday, except part of one Sunday, when grass was very scarce where we camped on Saturday night. The next morning we hooked up and found grass about 10 o’clock, and camped for the rest of the day. Sunday was our day for cooking beans and eating pickles. We never ate pickles except on Sunday.”[ii]

The episode of a murder and trial at Green river crossing is related by Delano[iii]. “Soon after my arrival, the whole encampment was thrown into great excitement by a cruel and fiendish murder, which was committed on the west bank. A reckless villain, named Brown requested a young man who acted as cook in his mess, to get him a piece of soap. The young man was at the moment bending over the fire, engaged in preparing the meal, and replied by telling him to get it himself, as he was busy. Without further provocation, as it appeared, the wretch raised his knife and stabbed him in the back killing the young man almost instantly. The murderer fled. A meeting of emigrants was called, and General Allen, from Lewis County, Missouri was called to the chair, when the atrocious deed was set forth, and it was determined by a series of resolutions to arrest the villain, give him a fair trial, and if found guilty, to execute him on the spot.. Major Simonton seconded the views of the emigrants in order to protect them against similar assassinations. In addition to a dozen athletic volunteers, who stood forth at the call, he detailed a file of soldiers to assist in the capture of the murderer. Several murders had been committed on the road a, and all felt the necessity of doing something to protect themselves, where there was no other law but brute force. The party set out in pursuit of Brown, and I lounged around among the different camps till afternoon, when our train came up, and established an encampment on the river bank among the crowd, from which we experienced much courtesy.”

‘The volunteers had returned, without being successful in capturing Brown, but they had overtaken Williams, who had killed the rascal at the Devil’s Gate, and thinking that some example of justice was necessary, they intimated that his presence was required to stand trial before a Green River jury, and he willingly returned; but his companions, dreading delay, would not accompany him. Upon his return it was resolved to try him. As his witnesses would not come, he feared a true representation of facts would not come out, and he employed B. F. Washington, Esq. to defend him. Had he known, there were witnesses enough in the crowd to have justified him, but as he did not, he was disposed to take advantage of any technicality, and therefore employed counsel.”

“A court of inquiry was organized; General Allen elected chief justice, assisted by Major Simonton, who with many of his officers, and a large crowd of emigrants, was present. A jury was empaneled, and court opened under a fine clump of willows. There, in that primitive court-house, on the bank of the Green River, the first court was held in this God-forsaken land, for the trial of a man accused of the highest crime. At the commencement, as much order reigned as in any lawful tribunal of the States. But, it was the 4th of July, and the officers and lawyers had been celebrating it to the full, and a spirit other than that of ’76 was apparent.”

“Washington, counsel for the defendant, arose and in a somewhat lengthy and occasionally flighty speech, denied the right of the court to act in the case at all. This, as a matter of law, was true enough, but his remark touched the pride of the old commandant, who gave a short, pithy, and spirited contradiction to some of the learned counsel’s remarks. This elicited a spirited reply, until, spiritually speaking, the spirits of the speakers ceased to flow in the tranquil spirit of the commencement, and the spirit of contention waxed so fierce, that some of the officer’s spirits led them to take up in Washington’s defense. From taking up words, they finally proceeded to take up stools and other belligerent attitudes. Blows, in short began to be exchanged, the cause of which would have puzzled a “Philadelphia Lawyer” to determine when the emigrants interfered to prevent a further ebullition of patriotic feeling, and words were recalled, hands shaken , a general amnesty proclaimed , and this spirited exhibition of law, patriotism “vi et armis” , was consigned to the “vastly deep.” Order and good feeling “once more reigned in Denmark.” Williams, in the meantime, seeing that his affair had merged into something wholly irrelevant, with a sort of tacit consent, withdrew, for his innocence was generally understood, and no attempt was made to detain him. The sheriff did not even adjourn the court, and it may be in session to this day, aught I know.” [At this point, the editor deems it relevant to note that Delano’s account of the journey frequently sacrificed fact for fanciful humorous elaboration.]

Down the Humboldt to the Desert

After the fourth, the company left the Green River and the journey continued to Fort Hall in Oregon from where they followed the Snake River. At Goose Creek they struck a southwestward course. The wagon train soon came upon the Humboldt River, a large, beautiful stream. Near its source the Humboldt River is fresh, cool, and reasonably full of water. But as it flows through the sun-scorched, alkali-impregnated country, it grows drearier to the eye. Emigrants detested it. It made more severe demands on their stamina than other parts of the journey. They knew that the worst hurdle of all, the Humboldt desert, awaited them at the end. The great desert of the Humboldt was marked by the place where the Humboldt River sunk out of sight. The desert crossing would take 48 hours of continuous travel to cross in searing heat without grass or water. Following the Humboldt Desert, the second foreboding obstacle the wagon train would encounter would be the great rock barrier presented by the Sierra Nevada Mountains -- the obstacle that trapped the Donner party in harsh weather in its deeply snow covered heights.

While gunshot accidents were a cause of almost daily casualties along the trail among the many wagon trains, the Charlestown Company completed four fifths of its journey without any injury from this source. It was true that Doctor Bryarly once discharged his pistol accidently, singeing B. F. Washington’s hair and putting a bullet through James Cunningham’s pantaloons but all gunshot injury had been avoided until the Company reached the Sink of the Humboldt. It was there that a young member of the company was accidentally shot and killed.

Emigrants in the valley of the Humboldt tended to regard all the Indians of that area as Shoshokees or “diggers”—a wretched, degraded, and despicable tribe, who were held guilty of making raids upon cattle. Another tribe, the Utes, a warlike group, was proficient in the art of cattle stealing. Since they usually struck at night, it was supposed that their crimes were committed by the Shoshokees who were apparent by day.

Wednesday, August 8th, Dr. Bryarly[iv] tells of his advance patrol to find water and grass for the animals. “I was anxious to get over this 10 miles to the slough in the cool of the morning, & to get our mules to the grass as soon as possible. I started ahead, upon my “Walking Squaw” (an Indian pony obtained from the Sioux), “Old Squaw”, with her nation’s instinct, & aided by her natural one, discovered its direction sooner than myself. When four miles from it, she would stop suddenly &, raising her head high, would sniff the breeze & seem to be drinking with delight the passing fragrance of the atmosphere. In due time I reached the spot on the plain and found it surpassing anything that I heard, in respect to the quality & quantity of grass.”

“This marsh [at the edge of the Humboldt sink] for three miles is certainly the liveliest place that one could witness in a lifetime. There is some two hundred and fifty wagons here all the time. Trains going out and others coming in; … It is rather amusing to see the many different manners which necessity has compelled the poor fellows to travel—some packing upon their back, others driving a half-dead mule or pony before them, laden with a few hard crackers & a coffee pot. There are carts of all descriptions, wagons that have been divided, one party taking the fore wheels & half the bed, another [taking]the hind ones with the remaining half. ‘Necessity is the mother of invention’, & if anybody doubts this, I think it well be convincing to them to be upon this road”.

“Arriving at the edge of the Humboldt desert, the company camped to rest their mules, to cut hay, and fill our kegs with water to cross the desert. It was a wide pretty valley with fine grass. The mules were turned loose to graze and a young man by the name of Joe Davis, and myself, were put on guard. It was a very hot day. Near where we were there was a large sage bush. The mules were grazing quietly, and he and I got under this sage bush to protect our heads from the sun. We each had our double barreled shotgun. We were there quite a while talking and noticed that the mules were straying a little too far off. We got up to walk around them. Davis had his gun by the side of him, with the breech towards the bush. He took hold of the barrel of the gun as he got up, and the hammer caught on a little twig on the bush. Down fell the percussion cap and the gun was discharged, the load going into his side just above the hip. I ran out and waved my hat; the boys were near camp, cutting hay, and filling the kegs with water. They heard the report of the gun. Quite a number of them came running to where we were. I told the boys that Joe had shot himself. They ran back to camp, got a blanket … [and summoned Doctor Bryarly]. They returned and packed him to camp on the blanket. He lived four hours. The doctor could do nothing to save his life.” [v]

“Like some vast, deliberately contrived obstacle course, the trail first exhausted the reserve strength of men and beasts along the Humboldt, and then subjected them to two supreme tests—the Humboldt Desert and the Sierra Nevada. The Desert presented a sixty five mile stretch of heat and sand, without wood or water, save for the noxious fluid of a single boiling spring. It required fifty-two hours of almost uninterrupted travel to make this crossing. Alternative roads led either to the Carson River, or Truckee River which was also known as the Salmon Trout River. The Charlestown Company chose the route to the Truckee, where they found the respite of cool water and green grass. But they could not linger long while the Sierra crossing still remained. This immense granite barrier required travel up grades steeper and along ledges narrower than any Forty-niner would have believed possible when he left Missouri. But great as were the difficulties, there was also great stimulus, for the ‘Diggings,’ the deposits of gold which had drawn men from the Old World and from below the Equator, lay just beyond the ride.”[vi]

Humboldt Desert

Saturday, August 11th dawned fair and beautiful. Everybody in active participation for a start across the desert had filled wagons with grass; casks, kegs, coffee pots and tea kettles were filled with water. Twelve miles in brought them to the “sink” extending over miles and miles without a vestige of vegetation, but so white and dazzling in the sun as to scarcely be looked at. Immense basins on all sides which receive back water seasonally, but which could not be consumed by man or beast. All along the desert road the wayside was strewn with dead bodies of oxen, horses, mules; the stench was terrible. Wagons and property of every description was abandoned and left strewn amongst the dead and dying animals.

Hot Springs is the only natural source of water along the trail through the Humboldt Desert. The water when cooled was drinkable but sulfurous and very salty. A piece of meat held in the boiling spring was perfectly done in twenty minutes. The water did not improve when dead animals and other debris accumulated in the spring. Some twenty miles beyond the Hot Springs, the Charlestown Mining Company wagon train came to the Truckee River having safely crossed the Humboldt Desert.[vii]

The company was overtaken by a friend of B. F. Washington, a Mr. Long, from Virginia or Maryland. He was traveling upon pack mules and invited Mr. Washington to accompany him to the “Diggings”. He said he expected to arrive at the “Diggings” a week before the wagon train.

Sierra Nevada Crossing

Upon reaching Donner Lake and the nearby pass over the height of the Sierras, the company was elated and joyous, thinking they had crossed the most difficult part of the traverse over the Sierras. Hoping to celebrate their accomplishments, Dr. Bryarly unpacked his reserved bottle of cognac and invited his mess to join him in a drink. Alas, the cork had been faulty and the empty bottle deflated their spirits and was perhaps an omen that foretold the gruesome and arduous descent from the crest of the Sierras. The road was up and down hill and rougher than they had seen before. One long descent over immense large rocks was so rough and steep that they had to let their wagons down by ropes. They met men on their return from the “Diggings”. Their news from the “Diggings” was extremely encouraging, but their account of the road ahead was appalling. The road ahead presented more slopes of greater steepness over rocks of immense size and roughness. The mules were unhitched from the wagons. The wagons were attached to ropes; the ropes, wound around large trees, were played out gradually to let the wagons down, not without an occasional mishap but without disastrous accidents. After a week-long arduous journey down the slope of the Sierra Nevada, the company arrived at the “Diggings”.[viii]

[i] McIlhany, Edward Washington, 1908, Recollections of a ‘49er, A Quaint and Thrilling Narrative of a Trip Across the Plains, and the Life in the California Gold Fields During the Stirring Days following the Discovery of Gold in the Far West, Hailman Printing Company, Kansas City, Missouri, 212p.

[ii] McIlhany, Edward Washington, 1908, Recollections of a ‘49er, A Quaint and Thrilling Narrative of a Trip Across the Plains, and the Life in the California Gold Fields During the Stirring Days following the Discovery of Gold in the Far West, Hailman Printing Company, Kansas City, Missouri, 212p., p. 23-24.

[iii] Delano, A., 1857, Life on the Plains and Among the Diggings; being Scenes and Adventures of an Overland Journey to California: Miller Orton & Co., 384 p., p. 125-127.

[iv] Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p., pp. 182-183.

[v] McIlhany, Edward Washington, 1908, Recollections of a ‘49er, A Quaint and Thrilling Narrative of a Trip Across the Plains, and the Life in the California Gold Fields During the Stirring Days following the Discovery of Gold in the Far West, Hailman Printing Company, Kansas City, Missouri, 212p., pp. 24-25.

[vi] Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p., p. 187.

[vii] Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p.

[viii] Potter, David Morris, 1945, Trail to California the overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly Edited with an Introduction: Yale University Press, New Haven, 266 p.

The Charlestown Company wagon train arrived at the Green River Monday, July 2nd. McIlhany[i] relates the arrival and the crossing of the Green River using the pontoons with which the company had come equipped.

“We finally reached Green River, which is in Utah. A large Beautiful valley with a pretty stream. Here we first used our iron boats in crossing a stream. We placed everything in the boats except the mules and horses, and they swam the river. There we made our camp. The next day was the fourth of July, and there were a great many emigrants there resting. Up and down the stream they were camped about, three thousand strong. We rested all that day, engaged in cooking, sewing, and washing. Tom Moore, from Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, was selected as orator of the day. He stood on a large stump and had an Indian pole in his left hand to steady himself with. Being the Fourth of July, our quartermaster issued some whisky rations. Some had more or less, and some didn’t drink. We hadn’t had our little cannon out of the wagon since we started, and we concluded that we would take it out that day and chain it to the stump. Moore felt pretty good, felling the effects of his whisky, and every time that he would say anything patriotic would touch the little cannon off, and the echo would bellow up and down the valley. The Indians, when they heard that cannon, would not come anywhere near us. They got out of the way. Some of the boys concluded that they would steal the cannon and throw it into the river, so that they would no haul it any further. Others found out what they were up to and blocked their game, putting the little cannon back in the wagon.

“There were many there that never had seen or heard of a cannon before, and they were very much interested in the proceedings of the day. It was a day that we all enjoyed very much. Although extremely anxious to get to the promised land of gold, nevertheless we always enjoyed a rest. We never traveled on Sunday, except part of one Sunday, when grass was very scarce where we camped on Saturday night. The next morning we hooked up and found grass about 10 o’clock, and camped for the rest of the day. Sunday was our day for cooking beans and eating pickles. We never ate pickles except on Sunday.”[ii]

The episode of a murder and trial at Green river crossing is related by Delano[iii]. “Soon after my arrival, the whole encampment was thrown into great excitement by a cruel and fiendish murder, which was committed on the west bank. A reckless villain, named Brown requested a young man who acted as cook in his mess, to get him a piece of soap. The young man was at the moment bending over the fire, engaged in preparing the meal, and replied by telling him to get it himself, as he was busy. Without further provocation, as it appeared, the wretch raised his knife and stabbed him in the back killing the young man almost instantly. The murderer fled. A meeting of emigrants was called, and General Allen, from Lewis County, Missouri was called to the chair, when the atrocious deed was set forth, and it was determined by a series of resolutions to arrest the villain, give him a fair trial, and if found guilty, to execute him on the spot.. Major Simonton seconded the views of the emigrants in order to protect them against similar assassinations. In addition to a dozen athletic volunteers, who stood forth at the call, he detailed a file of soldiers to assist in the capture of the murderer. Several murders had been committed on the road a, and all felt the necessity of doing something to protect themselves, where there was no other law but brute force. The party set out in pursuit of Brown, and I lounged around among the different camps till afternoon, when our train came up, and established an encampment on the river bank among the crowd, from which we experienced much courtesy.”

‘The volunteers had returned, without being successful in capturing Brown, but they had overtaken Williams, who had killed the rascal at the Devil’s Gate, and thinking that some example of justice was necessary, they intimated that his presence was required to stand trial before a Green River jury, and he willingly returned; but his companions, dreading delay, would not accompany him. Upon his return it was resolved to try him. As his witnesses would not come, he feared a true representation of facts would not come out, and he employed B. F. Washington, Esq. to defend him. Had he known, there were witnesses enough in the crowd to have justified him, but as he did not, he was disposed to take advantage of any technicality, and therefore employed counsel.”

“A court of inquiry was organized; General Allen elected chief justice, assisted by Major Simonton, who with many of his officers, and a large crowd of emigrants, was present. A jury was empaneled, and court opened under a fine clump of willows. There, in that primitive court-house, on the bank of the Green River, the first court was held in this God-forsaken land, for the trial of a man accused of the highest crime. At the commencement, as much order reigned as in any lawful tribunal of the States. But, it was the 4th of July, and the officers and lawyers had been celebrating it to the full, and a spirit other than that of ’76 was apparent.”

“Washington, counsel for the defendant, arose and in a somewhat lengthy and occasionally flighty speech, denied the right of the court to act in the case at all. This, as a matter of law, was true enough, but his remark touched the pride of the old commandant, who gave a short, pithy, and spirited contradiction to some of the learned counsel’s remarks. This elicited a spirited reply, until, spiritually speaking, the spirits of the speakers ceased to flow in the tranquil spirit of the commencement, and the spirit of contention waxed so fierce, that some of the officer’s spirits led them to take up in Washington’s defense. From taking up words, they finally proceeded to take up stools and other belligerent attitudes. Blows, in short began to be exchanged, the cause of which would have puzzled a “Philadelphia Lawyer” to determine when the emigrants interfered to prevent a further ebullition of patriotic feeling, and words were recalled, hands shaken , a general amnesty proclaimed , and this spirited exhibition of law, patriotism “vi et armis” , was consigned to the “vastly deep.” Order and good feeling “once more reigned in Denmark.” Williams, in the meantime, seeing that his affair had merged into something wholly irrelevant, with a sort of tacit consent, withdrew, for his innocence was generally understood, and no attempt was made to detain him. The sheriff did not even adjourn the court, and it may be in session to this day, aught I know.” [At this point, the editor deems it relevant to note that Delano’s account of the journey frequently sacrificed fact for fanciful humorous elaboration.]

Down the Humboldt to the Desert

After the fourth, the company left the Green River and the journey continued to Fort Hall in Oregon from where they followed the Snake River. At Goose Creek they struck a southwestward course. The wagon train soon came upon the Humboldt River, a large, beautiful stream. Near its source the Humboldt River is fresh, cool, and reasonably full of water. But as it flows through the sun-scorched, alkali-impregnated country, it grows drearier to the eye. Emigrants detested it. It made more severe demands on their stamina than other parts of the journey. They knew that the worst hurdle of all, the Humboldt desert, awaited them at the end. The great desert of the Humboldt was marked by the place where the Humboldt River sunk out of sight. The desert crossing would take 48 hours of continuous travel to cross in searing heat without grass or water. Following the Humboldt Desert, the second foreboding obstacle the wagon train would encounter would be the great rock barrier presented by the Sierra Nevada Mountains -- the obstacle that trapped the Donner party in harsh weather in its deeply snow covered heights.

While gunshot accidents were a cause of almost daily casualties along the trail among the many wagon trains, the Charlestown Company completed four fifths of its journey without any injury from this source. It was true that Doctor Bryarly once discharged his pistol accidently, singeing B. F. Washington’s hair and putting a bullet through James Cunningham’s pantaloons but all gunshot injury had been avoided until the Company reached the Sink of the Humboldt. It was there that a young member of the company was accidentally shot and killed.

Emigrants in the valley of the Humboldt tended to regard all the Indians of that area as Shoshokees or “diggers”—a wretched, degraded, and despicable tribe, who were held guilty of making raids upon cattle. Another tribe, the Utes, a warlike group, was proficient in the art of cattle stealing. Since they usually struck at night, it was supposed that their crimes were committed by the Shoshokees who were apparent by day.

Wednesday, August 8th, Dr. Bryarly[iv] tells of his advance patrol to find water and grass for the animals. “I was anxious to get over this 10 miles to the slough in the cool of the morning, & to get our mules to the grass as soon as possible. I started ahead, upon my “Walking Squaw” (an Indian pony obtained from the Sioux), “Old Squaw”, with her nation’s instinct, & aided by her natural one, discovered its direction sooner than myself. When four miles from it, she would stop suddenly &, raising her head high, would sniff the breeze & seem to be drinking with delight the passing fragrance of the atmosphere. In due time I reached the spot on the plain and found it surpassing anything that I heard, in respect to the quality & quantity of grass.”

“This marsh [at the edge of the Humboldt sink] for three miles is certainly the liveliest place that one could witness in a lifetime. There is some two hundred and fifty wagons here all the time. Trains going out and others coming in; … It is rather amusing to see the many different manners which necessity has compelled the poor fellows to travel—some packing upon their back, others driving a half-dead mule or pony before them, laden with a few hard crackers & a coffee pot. There are carts of all descriptions, wagons that have been divided, one party taking the fore wheels & half the bed, another [taking]the hind ones with the remaining half. ‘Necessity is the mother of invention’, & if anybody doubts this, I think it well be convincing to them to be upon this road”.